I’ve recently joined a psychoanalytic film club where our focus is on discussing various films. During our inaugural session, we delved into the intricacies of “Adieu Lacan” (2022), a film centered around the psychoanalytic treatment of a woman. This narrative might particularly intrigue those who are already engaged in clinical psychoanalysis. Interestingly, psychoanalytic film theory is a recognized discipline, enabling the application of theoretical concepts from one realm to another, leading to captivating artistic expressions.

While this endeavor may hold limited clinical implications, it’s essential to acknowledge that cinematic exploration cannot substitute for understanding the complexities of individuals, their psychological mechanisms, or psychopathologies. However, the fusion of cinema and theoretical frameworks provides a compelling avenue to comprehend characters and their fantasies, often yielding moments of engagement and inspiration. Certain films, such as “The Patience Stone” (2012), have personally motivated me, catalyzing a desire to depart from mundane corporate work and embark on a more meaningful path.

Just like any art form, cinema demands interpretation. Psychoanalytic theory, in this context, serves as a potent tool to narrate or reinterpret stories through the eyes of a spectator. It’s important to note that the clinical realm employs a different approach. In psychoanalytic sessions, individuals have the autonomy to voice their thoughts, while exploration is encouraged from the perspective of a psychoanalyst.

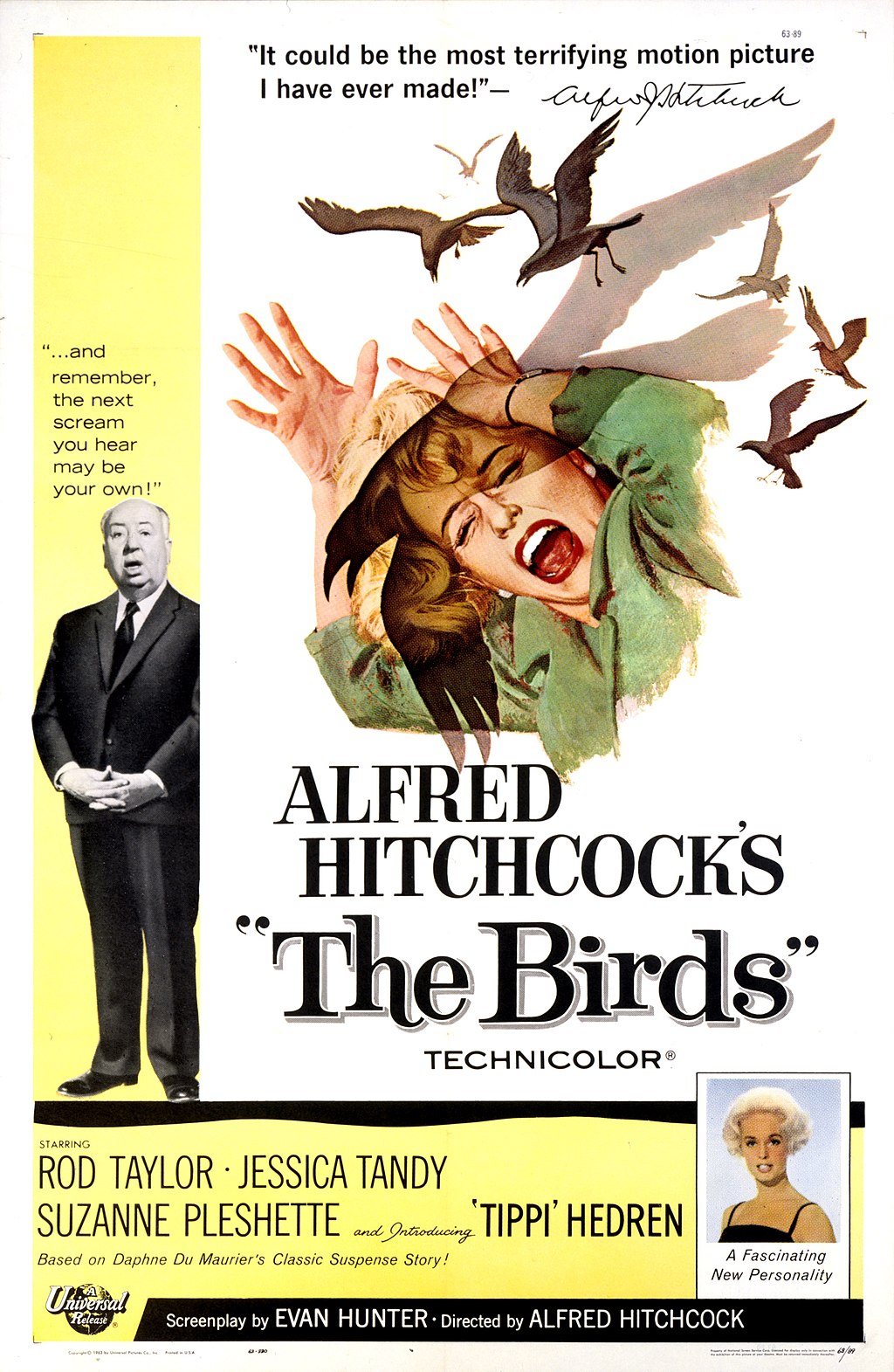

This week, our club turned its attention to “Birds” (1963), a departure from my usual cinematic preferences. Reflecting on the cultural contexts inherent in film symbolism, the unspoken rules of scripting, and the intricate interplay among spectators, markets, investors, and audiences that shape a film’s trajectory, I recognized the diverse sensations evoked by French, German, and Iranian cinema.

In a lighthearted approach, I set aside judgment during the 1960s American film “Birds.” It leads one to ponder whether enriching the scriptwriting process by involving psychoanalysts might elevate cinema to a new level. This notion isn’t entirely novel; past instances, such as the ‘In Treatment’ series, had analyst input. This collaboration could potentially remedy character and dialogue scripting shortcomings, offering heightened suspense. Unlike stifling desire, psychoanalysts thrive on individuals elaborating their fantasies. However, in Hitchcock’s scripting, I experienced a slight sense of suffocation, with overt explanations and a lack of nuanced elaboration.

Within the film, the character portraying the mother asserts her “dependence” on her lawyer son. Though presented as protective and nurturing, she paradoxically exhibits an apparent readiness to detach from her son and welcome a new woman during a brief weekend encounter.

The film introduces a cast of intricate characters, whose complexity could have been moderated through further development of key traits. While the relationship dynamics between mother and son, and the entry of Melanie into the town, appeared significant, the narrative swiftly abandoned this thread, shifting focus to the town’s confrontation with an overwhelming influx of birds. While parallels between avian entry and the new woman’s arrival hint at emerging issues within maternal bonds and town dynamics, these connections remained underexplored.

The script’s potential threads, carefully woven by the director’s vision, felt somewhat rushed and left unfulfilled. While a caring connection seemed to form between the mother and Melanie, it contradicted the physical boundaries set by their dialogues. Such inconsistencies hindered a sense of temporal progression.

In contrast, masterful scripts, such as those by Asghar Farhadi, employ subtle cues to denote the passage of time, inviting viewers to engage with their own interpretations. In “Birds,” opportunities to exploit doubts and fantasies within the script were underutilized. Akin to Quentin Tarantino’s work, which offers a continuous element of surprise, a scene depicting the gathering of crows outside a classroom window stands out. Here, Melanie’s isolation amid a crow-infested scene evokes an enticing sense of doubt and hallucinatory intrigue, resonating with moments of human stress.

During a particular scene, the mother confides her high dependence on her son to Melanie. Such revelations, typical in therapeutic settings, remain guarded with strangers, making this scripting choice intriguing. However, the film missed the opportunity to unveil the women’s vulnerabilities through interactions and character dynamics.

The portrayal of rivalry between the two women left room for further exploration. Contemporary cinema, exemplified by films like “The Black Swan” (2010), adeptly delves into rivalry and hallucinatory events, providing a more vivid depiction. A potential link between the birds and the hostility between the mother and Melanie remains ambiguously defined. The film could have skillfully cultivated uncertainty around the birds’ existence—were they real, imaginary, or symbolic of animosity towards the unfamiliar?

The film’s narrative, where Melanie’s entry coincides with the town’s social breakdown, parallels her role in unsettling the fabric of the community. The interplay between characters’ relationships and the symbolic law becomes evident, suggesting that Melanie’s presence disrupts the town’s equilibrium—could the birds represent her influence?

The lawyer’s evolving trust in Melanie, juxtaposed with the escalating chaos, raises questions about their dynamic. Notably absent is a portrayal of the love that blossoms between them, setting the stage for the film’s central metaphor. The crescendo of ‘love birds’ culminates in the town’s ruin and the characters’ destruction—a chilling metaphor for being consumed by the maddening effects of being in love.

Ultimately, “Birds” raises inquiries into the depths of human vulnerability, anxiety, and the unpredictable consequences of connection. The film’s ability to evoke such unsettling themes showcases the power of cinema to reflect profound psychological experiences.

In another interpretation, Melanie’s symbolic destabilization of the town leads to a depiction of the man’s inner turmoil. The attack of the birds becomes a metaphor for his vulnerability in relation to Melanie, representing a turmoil he struggles to navigate. This discomfort hints at the unease between them, where an unusual attachment emerges—symbolized by his insistence on her presence.

As the film’s enigmatic elements unfold, Melanie’s impact is undeniable. A single line from a restaurant guest, accusing her of inciting the bird attacks, raises intriguing possibilities. Echoing back to the film’s outset, her connection to deception and betrayal amplifies, suggesting a manifestation of the characters’ internal struggles through avian symbolism.

The evolution of trust between the lawyer and Melanie further underscores their complex relationship. Their journey, marked by destruction and eventual dissolution, paints a poignant metaphor for the consuming nature of love. The film leaves us pondering the birds’ role—do they mean anxiety, phobia, or hallucination?

In a different light, Melanie’s entrance into the town disturbs its order, paralleling her symbolic influence on the lawyer’s life. Her destabilizing effect reflects his internal conflict, exposing his vulnerabilities. Their relationship, fraught with unease, finds resonance in the surreal scene of Melanie’s presence becoming a calamitous dinner.